What Drives People to Send Their Devices Back to Producers?

Brought to you by Christiane Lehrer from Copenhagen Business School, Christian Meske and Hüseyin H. Keke from Ruhr-Universität Bochum

How can the growing e-waste challenge be addressed?

Electronic waste, or e-waste, is becoming an increasingly significant global issue. The number of electronic devices continues to grow, while recycling rates remain low. This leads to improper disposal of unused devices, which not only harms the environment but also results in the loss of valuable raw materials (He et al., 2023; Ni et al., 2023).

Achieving a sustainable product lifecycle requires shifting from a “take-make-dispose” linear economy to a circular economy. In a circular model, products are designed to be reused, refurbished, or recycled, keeping materials in circulation and reducing waste. This approach extends the life of electronic devices, promotes resource recovery, and minimizes environmental impact. Strategies such as modular design, ease of repair, and business models like leasing help keep products in use longer, closing the loop and creating a more sustainable system for electronic devices (Kirchherr et al., 2017). A widely used approach to keep devices in the lifecycle or extend their use is through take-back programs. These programs mandate that producers design electronics for easier recycling and provide take-back services, which facilitates, for example, reuse or remanufacturing, thereby supporting a circular economy. Nevertheless, the consumer remains critical in this process, as they ultimately determine whether a device is returned to the loop or disposed of as waste (Li et al., 2021).

What psychological factors influence the success of take-back programs?

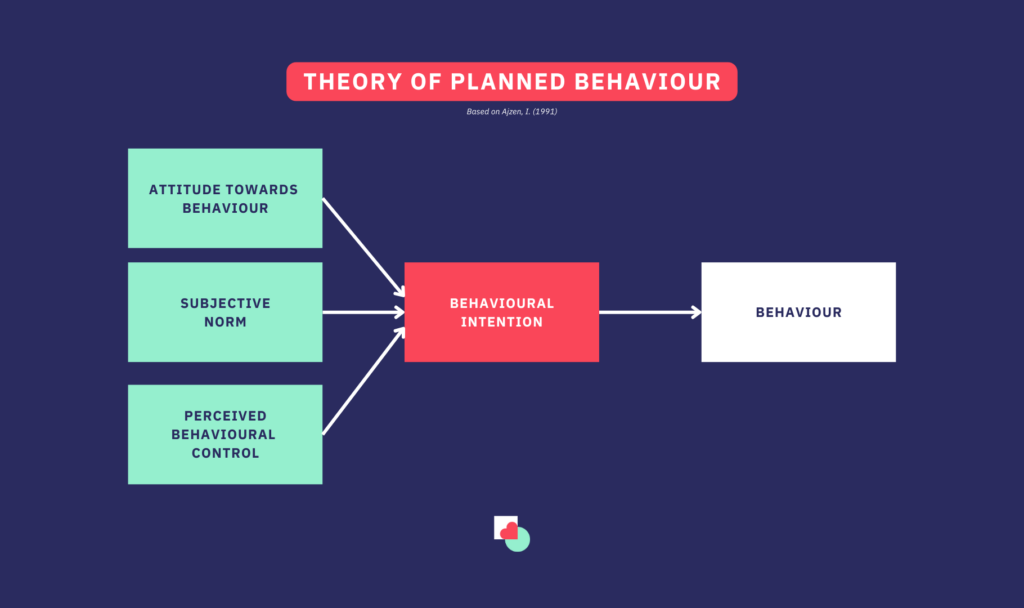

Understanding the motivations behind sustainable behaviour, particularly in the context of e-waste, requires insight into the psychological factors that drive individuals to act. One of the most successful theories in explaining motivations for sustainable behaviour is the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). This well-established framework has been applied in various fields of research and has proven effective in explaining why people act the way they do (e.g., Puzzo & Prati, 2024). It consists of three main components: attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen, 1991). This raises the question: what exactly do these three components represent?

- Attitude refers to a person’s positive or negative evaluation of their behaviour. For instance, if someone believes that recycling electronic devices benefits the environment, they are likely to have a positive attitude towards participating in take-back programs.

- Subjective Norm involves the perceived social pressure to perform or avoid a behaviour. If individuals feel that their friends or community support recycling, they may feel encouraged to return their devices.

- Perceived Behavioural Control relates to a person’s belief in their ability to perform the behaviour. If someone believes they can easily access take-back programs and understand the recycling process, they are more likely to participate.

Together, these components influence the intention to act, with strong positive attitudes, supportive norms, and high perceived control increasing the likelihood of engaging in sustainable behaviours (Ajzen, 1991) like return electronic devices (Dixit & Badgaiyan, 2016).

Beyond psychology: What other factors support effective take-back programs?

Beyond these psychological factors, other facilitating factors also play a role in shaping individuals’ intentions to engage in sustainable actions. In the context of e-waste, research has identified several relevant factors. Among the most important factors is convenience (Puzzo & Prati, 2024). When the process of returning devices is straightforward and accessible—such as through nearby drop-off points or user-friendly return options—it significantly increases the likelihood that individuals will participate in sustainable e-waste disposal. This ease of access makes the process hassle-free, encouraging more people to engage in sustainable practices (Kim & Paulus, 2011; Laeequddin et al., 2022). Another factor that can significantly encourage e-waste returns, yet has received relatively little attention, is the use of producer interventions. These could include support such as manufacturer helplines, clear return instructions, or return symbols on the products, all of which can guide consumers through the process and make it more accessible (Laeequddin et al., 2022).

What are our takeaways?

In conclusion, addressing the growing e-waste problem requires a shift toward a circular economy, where devices are designed for reuse, refurbishment, or recycling. While strategies like take-back programs are crucial, consumer participation is essential to ensure that devices re-enter the loop.

Understanding psychological drivers, such as attitude, social norms, and perceived control, helps to motivate sustainable behaviours. Additionally, factors like convenience and producer interventions can further facilitate e-waste returns, making it easier for individuals to engage in responsible disposal practices and contribute to a more sustainable future. Academically, we can benefit by not limiting ourselves to a single discipline, but rather by leveraging insights from various fields to expand our body of knowledge.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

He, Y., Kiehbadroudinezhad, M., Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H., Gupta, V. K., Peng, W., Lam, S. S., … & Aghbashlo, M. (2023). Driving sustainable circular economy in electronics: A comprehensive review on environmental life cycle assessment of e-waste recycling. Environmental Pollution, 123081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.123081

Kim, S., & Paulos, E. (2011). Practices in the creative reuse of e-waste. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2395-2404). https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979292

Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

Laeequddin, M., Kareem Abdul, W., Sahay, V., & Tiwari, A. K. (2022). Factors that influence the safe disposal behaviour of e-waste by electronics consumers. Sustainability, 14(9), 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094981

Li, B., Wang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2021). Managing a closed-loop supply chain with take-back legislation and consumer preference for green design. Journal of Cleaner Production, 282, 124481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124481

Ni, Z., Chan, H. K., & Tan, Z. (2023). Systematic literature review of reverse logistics for e-waste: Overview, analysis, and future research agenda. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 26(7), 843-871. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1993159

Puzzo, G., & Prati, G. (2024). Psychological correlates of e-waste recycling intentions and behaviours: A meta-analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 204, 107462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107462

Dixit, S., & Badgaiyan, A. J. (2016). Towards improved understanding of reverse logistics–Examining the mediating role of return intention. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 107, 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.021